The Art Of Becoming Human

By Pete Dolack

March 13, 2015 "ICH"

- "Systemic

Disorder" - About

180,000 people enlist in the United States

military each year, many of whom will come

home with physical injuries or psychological

damage. Recruits are trained to kill, taught

to de-humanize others, to participate in

torture, but are expected to forget upon

returning to civilian life.

That

22 veterans commit suicide per day is a

grim reminder not only of the harsh demands

of military life but that the Pentagon

effectively throws away its veterans after

using them. The U.S. government is quick to

start wars, but although political leaders

endlessly make speeches extolling the

sacrifices of veterans, it doesn’t

necessarily follow up those sentiments,

packaged for public consumption, with

required assistance.

Veterans themselves are

using art to begin the process of working

their way through their psychological

injuries in a program known as “Combat

Paper.” In an interesting twist on the

idea of beating swords into plowshares, the

Combat Paper program converts veterans’

uniforms into paper, which is then used as a

canvas for art works focusing on their

military experiences. Deconstructed fibers

of

uniforms are beaten into pulp using

paper-making equipment; sheets of paper are

pulled from the pulp and dried to create the

paper.

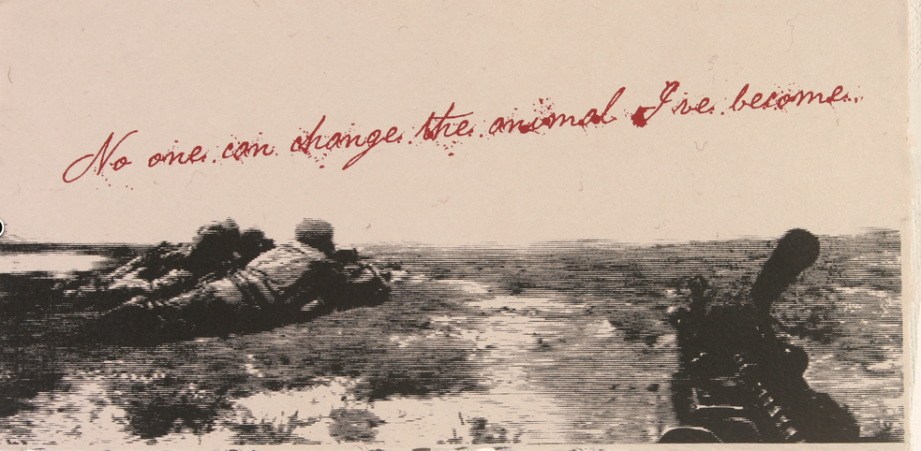

“No One Can Change The

Animal I’ve Become,” silkscreen, by

Jesse Violante

Drew Cameron, one of the

initiators of Combat Paper Project, writes

of the concept:

“The story of the

fiber, the blood, sweat and tears, the

months of hardship and brutal violence

are held within those old uniforms. The

uniforms often become inhabitants of

closets or boxes in the attic. Reshaping

that association of subordination, of

warfare and service, into something

collective and beautiful is our

inspiration.”

The results are dramatic,

as I found while viewing an

exhibit at the Art 101 gallery in New

York City’s Williamsburg neighborhood. Take,

for example, Jesse Violante’s silkscreen, “No

One Can Change The Animal I’ve Become.”

The title sentence is written in bloody red

letters above a scene of soldiers in an

exposed forward position, lying prone with

weapons ready. The image is stark, depicting

only the most immediate surroundings,

representing the lack of vision on the part

of officials who see war as a first option

and the fog of uncertainty as experienced by

the solider in the field reduced to a

scramble for survival.

Wounds that can be

seen and those not seen

There are those whose

injuries are obvious, such as Tomas Young,

whose struggles were shown in full intensity

in the documentary Body of War. In

the

letter he wrote to George W. Bush and Dick

Cheney when his death was impending, he

put into words his agony:

“Your cowardice and

selfishness were established decades

ago. You were not willing to risk

yourselves for our nation but you sent

hundreds of thousands of young men and

women to be sacrificed in a senseless

war with no more thought than it takes

to put out the garbage. I have, like

many other disabled veterans, come to

realize that our mental and physical

[disabilities and] wounds are of no

interest to you, perhaps of no interest

to any politician. We were used. We were

betrayed. And we have been abandoned.”

And there are those whose

injuries are not so immediately obvious.

Let’s hear from a couple of them. Kelly

Dougherty, who helped to found Iraq Veterans

Against the War after serving as a medic and

as military police, said she appreciates

having a space to “talk about my feelings of

shame for participating in a violent

occupation.”

She writes:

“When I returned from

Iraq ten years ago, some of my most

vivid memories were of pointing my rifle

at men and boys while my fellow soldiers

burned semi trucks of food and fuel, and

of watching the raw grief of a family

finding that their young son had been

run over and killed by a military

convoy.

I remember being

frustrated with military commanders that

seemed more concerned with decorations

and awards than with the safety of their

troops, and of finding out that there

never were any weapons of mass

destruction. I was angry and frustrated

and couldn’t relate to my fellow

veterans who voiced with pride their

feelings that they were defending

freedom and democracy. I also couldn’t

relate to civilians who would label me a

hero, but didn’t seem interested in

actually listening to my story.”

Garett Reppenhagen, also a

member of Iraq Veterans Against the War,

wrote on the group’s Web site about how the

resistance he received at Veterans

Administration meetings when he tried to

speak of his experiences, the illegality of

the Iraq occupation and the lies of the Bush

II/Cheney administration that started the

war. “The ‘you know you aren’t allowed to

go there’ look,”

as he

puts it:

“I can’t bring up the

child that exploded because she

unknowingly carried a bomb in her school

bag and how her foot landed next to me

on the other side of the Humvee. I can’t

talk about how we murdered off duty

Iraqi Army guys working on the side as

deputy governor body guards because they

looked like insurgents. I can’t talk

about blowing the head off an old man

changing his tire because he might have

been planting a roadside bomb. I can’t

talk about those things without talking

about why we did it.”

Fairy tales become

nightmares

Why was it done? United

States

military spending amounts to a trillion

dollars a year, more than every other

country combined. The invasion and

occupation of Iraq was intended to create a

tabula rasa in Iraq, with its economy

cracked wide open for U.S.-based

multinational corporations to exploit at

will, a neoliberal fantasy that extended

well beyond the more obvious attempt at

controlling Iraq’s oil. Overthrowing

governments through destabilization

campaigns, outright invasions and financial

dictations through institutions like the

World Bank and the International Monetary

Fund have long been the response of the U.S.

to any country that dares to use its

resources to benefit its own population

rather than further corporate profits.

And the fairy tales of

emancipating women from Muslim

fundamentalists? We need only ask, then, why

the U.S. funded and armed the Afghan

militants who overthrew their Soviet-aligned

government for the crime of educating girls.

Or why the U.S. government stands by Saudi

Arabia and other ultra-repressive

governments. Those Afghan militants became

the Taliban and al-Qaida, and spawned the

Islamic State. More interference in other

countries begets more resistance, more

extreme groups feeding on destruction and

anger.

What does it say about our

humanity when ever more men and women are

asked to bear such burdens, pay such high

prices for an empire that enriches the 1

percent and impoverishes working people,

including the communities from which these

soldiers come from. What does it say about

our humanity when the countries that are

invaded are reduced to rubble and suffer

casualties in the millions, and this is

cheered on like a video game?

“These Colors Run

Everywhere,” spray paint, by Eli Wright

All the more

thought-provoking are the art works of the

Combat Paper Project. Another work, “Cry For

Help” by Eli Wright, is of a man screaming

and a phone held by a skeletal hand and arm.

Barbed wire is stretched over the top. How

well would we hold on to our humanity had we

been on patrol? If we were at risk of being

killed at any time by such a patrol?

A second exhibit by Mr.

Wright is “These

Colors Run Everywhere,” a more

minimalist work that shows reds, whites and

blues dripping down the canvas, a rain

falling upon an urban landscape reduced to a

shadowy background that could be interpreted

as symbolic of the lack of knowledge of the

places that the U.S. invades and of the

societies that invasions destroy. It is also

a wry twisting of a common slogan used as a

defensive mantra into a doctrine of offense

and invasion, the actual practice of that

slogan.

I assuredly do not speak

for, could not speak for, these artists.

Perhaps you would have different, maybe very

different, interpretations. The movie

American Sniper, glorifying a racist

murderer and thus symbolizing the

dehumanizing tendencies of those who beat

their breasts while screaming “We’re number

one!” when the death toll climbs higher, has

taken in tens of millions of dollars. Vastly

less money will change hands as a result of

the Combat Paper artworks. But what price

should be paid for our humanity?

Combat Paper is

on display at Art 101 until April 5.

Pete Dolack, is an

activist, writer, poet and photographer. He

blogs at the

Systemic Disorder